VIGNETTE

Vignetting is an imaging phenomenon that happens with virtually every optical system and appears as a radial darkening of the image toward the periphery of the frame.

1. Natural Vignetting:

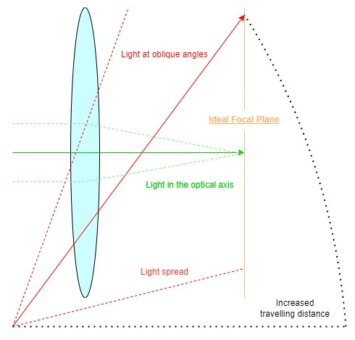

It is a result of the geometry of the optical system and the light falloff that naturally occurs as the angle of incidence increases towards the edges of the lens. This variation in angles causes radial dimming, because light incident at the edges of a film/sensor has to travel a longer distance than light incident in the center, thus becoming progressively dimmer. At the same time, light hitting the image center at normal incidence is stronger than striking the image corner at the angle (this can be compared to a late afternoon sun, which warms the earth less than the midday sun because the same beam of sunlight is spread over a larger area). Finally, the lens aperture (pupil), as seen by the light rays, is more elliptical and therefore narrower at an angle, compared to a wider circle straight on.

It is inherent to "any" lens design and most significant with wide-angle lenses. It cannot be stopped by reducing the aperture (higher f-stop) and is less pronounced on smaller camera sensors (due to the implicit reduction in the lens focal length).

Light at oblique angles distance

and dispersion

and dispersion

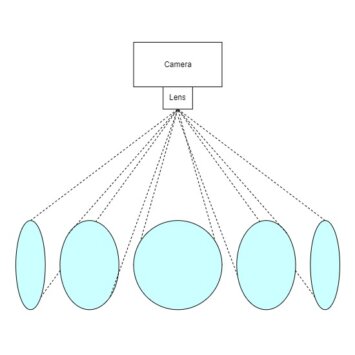

Lens seen at an angle

Sensor Crop

Natural Vignetting

2. Optical Vignetting:

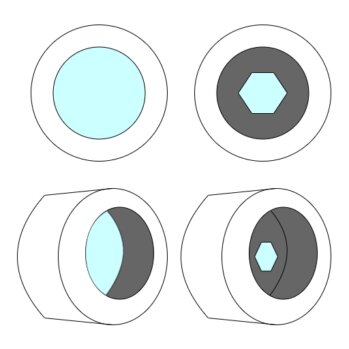

It may appear as a more abrupt darkening towards the edges of the image, exhibiting more distinct and pronounced darkening patterns, often circular, but could take on a slight polygonal shape (similar to the shape of the diaphragm) according to the lens design, although this type of pattern may most be virtually imperceptible to the human eye.

Optical vignetting tends to be stronger in wide-angle lenses, due to the larger covered field of view, although the effect can be noticed with most photographic lenses (e.g. zoom lenses tend to have fair amount of optical vignetting), and at large apertures. At the widest apertures, due to the length of the lens barrel, peripheral light rays travelling at extreme angles are partially blocked by the lens barrel itself. Consequently, the light that reaches the image plane at such angles naturally falls off (decreases in brightness) towards the extreme corners of the frame.

The remedy is to reduce the lens diaphragm (higher f-stop): the darkening observed at full aperture already improves greatly when the lens opening is decreased by one stop, and a complete cure often requires two or three stops depending on the design. The darkening that remains at small apertures is due to natural vignetting.

Comparison of wide vs narrow aperture, front vs sideways

Simulation of Optical Vignetting at f/1.4 vs f/5.6

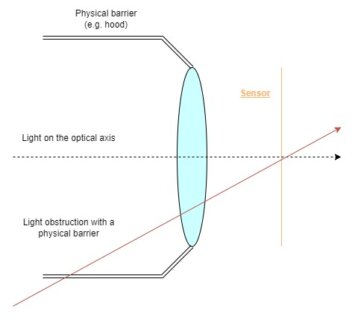

3. Mechanical Vignetting:

Mechanical obstruction

Mechanical Vignetting

4. Pixel Vignetting:

Specific to digital cameras, it is caused by angle dependence in the digital sensors. Light incident on the photo-diode at a right angle produces a stronger signal than light incident at an oblique angle. This results in darkening at the corners and edges of the image where light strikes at greater angles. Modern camera designs often incorporate micro-lenses over each pixel to help redirect angled light toward the photo-diodes, which helps mitigate this effect and/or automatically correct for it through in-camera processing. In some cases, pixel vignetting may contribute to color shifts if different color channels are affected unevenly.

Micro-lens array and angle of incidence

Pixel Vignetting